Sustainable Approaches to Public Safety in Today’s Environment

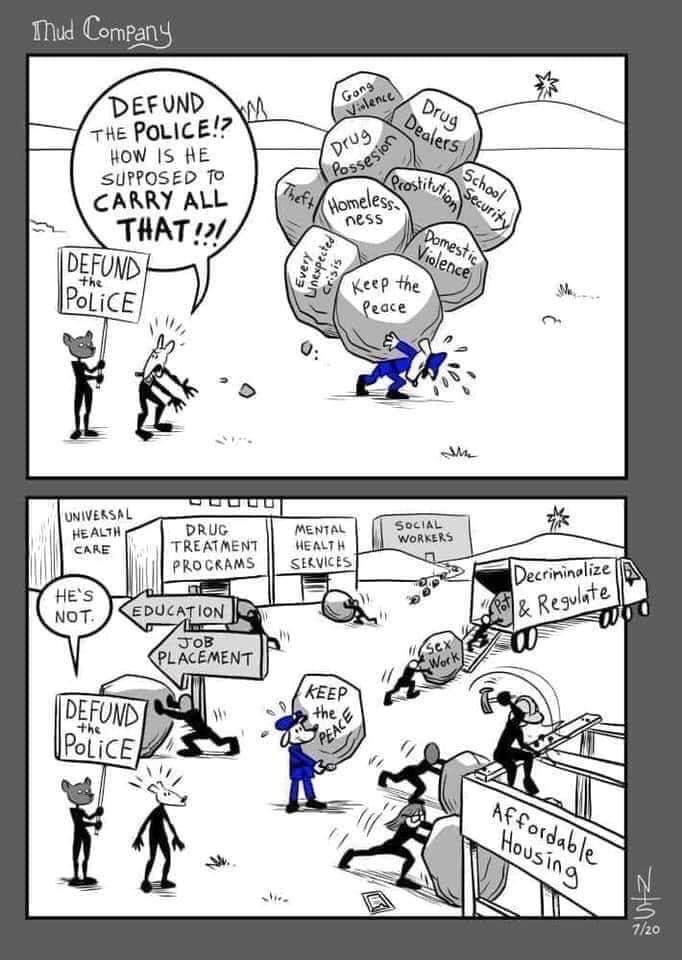

Heidi Voorhees sent me this graphic and it instantly resonated with my experiences as a career local government professional. Police Departments have been saddled with responsibilities well beyond that of peacekeeping. As laws and societal issues have become increasingly complex, local police officials have been asked to take on any number of additional roles – mentors, counselors, relationship experts, referral services, community advocates, code enforcement workers, etc.

Increasing the responsibilities for police officers has created many unintended consequences. The added demands make it progressively difficult to find qualified candidates who can: pass background checks, write coherent reports, use guns, and promise their undying loyalty to both the organizational hierarchy and the jurisdiction’s residents for what local governments are able and willing to pay. We find ourselves in a situation where even in those jurisdictions that can pay what it takes to get and retain a full complement of qualified officers, those communities might still find themselves with more intractable public safety problems than they desire. Officers feel like they are either warriors or social workers, but rarely both. (Police on Policing, The Unsung Consensus: Candid Conversations on the State of Law Enforcement in America, p.51)

Those on the front lines are left without good answers. Police and the local governments must combine traditional and expanded duties within the backdrop of institutional racism. While managing a lack of funding, they must employ a comprehensive strategy to address multi-faceted concerns like affordable housing, substance abuse, uneven educational opportunities, and unemployment/underemployment. Worse yet, a multiplicity of confrontations with police resulting in serious injury and death (sometimes over what appear to be relatively minor issues) have left large segments of our population in positions where they have no desire to build trusting or constructive relationships with police. Those residents are left alienated and resentful.

When I was in undergraduate school, I studied courses related to the formation of the first local governments. In brief, cities formed in large part around agriculture – large farms grew surplus food which meant you didn’t have to be your own farmer, which also meant you could move to a city where you could gain quick access to that food and obtain a job doing something else.

Once in the city, there was a need for laws and someone to enforce them: “Understood broadly as a deliberate undertaking to enforce common standards within a community and to protect it from internal predators, policing is much older than the creation of a specialized armed force devoted to such a task. The activity of policing preceded the creation of the police as a distinct body by thousands of years. The derivation of the word police from the Greek polis, meaning “city,” reflects the fact that protopolice were essentially creatures of the city, to the limited extent that they existed as a distinct body.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/police/The-history-of-policing-in-the-West

Unsurprisingly, early policing involved more mediation than coercion. Ironically, many of the ancient policing entities also carried other tasks – various functions that modern cities allocate to other government workers, such as tax and garbage collection, and firefighting. So, the early precursors to modern police provided most local government services, then governments streamlined police work to focus on crime-fighting, and as crime-fighting needs became more thorny, additional responsibilities were heaped on the shoulders of police to address.

It has become clear that those myriad duties might again be misplaced. Modern cities struggle with creating lasting approaches to public safety considering all that has transpired. Many elected and appointed leaders are re-thinking their position on police-community relations, police recruitment, training, and retention, and funding for the numerous disciplines that contribute to safer communities. Leaders undertaking this process must ask many questions of themselves, their constituents, and their law enforcement and non-law enforcement employees. The most important question is: how they will all work together to reduce crime? We frequently hear that “It takes a village to raise a child,” an African proverb that means that an entire community of people must interact with children for those children to experience and grow in a safe and healthy environment. We also have to come to the realization that it takes many departments and types of professionals to create a truly safe community.

Contact us at info@govhusa.com for more information on how we can help facilitate your community’s conversations around public safety in this new era.

Janice Allen Jackson is a Vice President at GovHR USA and owner of Janice Allen Jackson & Associates, LLC.

She has worked closely with public safety and human services in Albany, GA Charlotte-Mecklenburg, NC, and Augusta-Richmond County, GA.

![]()